01.

What's the story?

“A new form of arguing has been invented in our lifetimes - it's large, it's distributed, it's low cost, it's compatible with the ideals of democracy.

"The question for us now is, are we going to let the programmers keep it for themselves or are we going to try and press it into service of society at large?"

The birth and growth of computers, like maths and science, was open and collaborative – right back to Ada Lovelace’s work with Charles Babbage in the 19th Century. 20th Century pioneers like Alan Turing in Britain, John von Neumann and John W. Backus in America and Konrad Zuse in Germany built on each other's work. The giant IBM mainframes of the 50s were sold as hardware, with software bundled free alongside; the revolutionary BASIC language created at Dartmouth College in the 60s was not only without ownership – it inspired and helped thousands of new programmers. But in 1974 an amendment to the US Copyright Act added software for the first time, and the culture began to change.

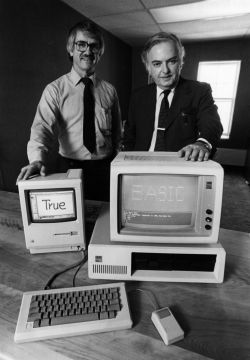

The following year Microsoft was born, offering a proprietary version of BASIC for the Altair 8800 on paper-tape. By the end of the year, Bill Gates likened the hobbyists, who had always copied paper-tape, to thieves. A few years later Steve Jobs convinced Steve Wozniak to close-source his design for the Apple 1 motherboard and the PC revolution of the 80s began, built around closed-source software.

But a counter-revolution was already underway, starting with the GNU Project, launched in 1983, the same year IBM stopped releasing the 'binaries' (aka source code) for their mainframes. Multiple projects to create an open source version of the mainframe language Unix bore fruit: Linux, building on the work of GNU and which forms the backbone of Android phones and much of the Internet's architecture; and BSD, which worked its way into Jobs' post-Apple computer NeXT and underpins iPhones. Tim Berners-Lee designed the Web on a NeXT and its freedom from copyright is central to its success: initially it was much like the early hobbyist computer industry, driven by academics, hackers and anarchists.

Meanwhile Linus Torvalds created a powerful system for distributed, decentralised collaboration to improve Linux called Git. Open Source stopped being a development philosophy, but a working methodology revolutionising development workflows, security and user engagement alongside a growth from object-oriented to modular and microservices architecture. In the last few years Red Hat Linux sold to IBM for $29bn and Github sold to Microsoft for $7.5bn. Microsoft conceded they ‘were wrong about Open Source’ and are open-sourcing ever more of their tools and systems.

Open Source isn’t just a business model for software, it’s a working methodology with transparency, freedom, open participation, meritocracy and distributed at its heart. From Open Data spanning government reporting to agriculture sustainability, with Wikimedia and Open Streetmap to Taiwan's g0v platform and open Covid19 resources and ventilator designs – open principles drive new collaborations and knowledge-sharing worldwide.

Still the conflict between open and closed continues. With the controversial inclusion of proprietary, encrypted DRM-code in the HTML specification for the first time, the web could risk locking out browser makers, and creating a closed ecosystem. Furthermore, as seen with the Heartbleed bug, vital open source software millions depend on can struggle to earn enough to pay the core maintainers for their work – creating a further challenge around sustainability.

This is the great contradiction at the heart of Open Source – it mashes up communism's rejection of private property with the unfettered free market principles of capitalism – there's huge and motivated volunteer communities and big corporate profits. What the Fork? wants to tell this history and get under the skin of the philosophy of a big idea that's bigger than technology.